Sanctuary Public Breastfeeding Seat

This seat attempts to meets the needs of breastfeeding mothers. The process was approached from an inclusive, ergonomic, physical comfort, perceptual, social, and safety perspective.

The Sanctuary Public Breastfeeding Seat was was the capstone project of my Bachelor of Industrial Design degree. In conjunction with a team, I had the opportunity to work with Ingenium Group’s Canada Science and Technology Museum to design and build inclusive seating solutions for its central Hub area. The primary goal was to create inclusive and accessible seating space that promotes a fun, family-friendly social environment. My personal scope was to create a chair that meets the needs of breastfeeding mothers.

The Sanctuary seat and one other student's work was selected by the CSTM to be housed in the museum's central space. Read more about the Sanctuary seat on the Ingenium Channel website and The Charleton. The Sanctuary seat in conjunction with a stool designed by Jenny Suh won third place in the 2018 IDeA awards. The Sanctuary seat was also a finalist in the 2019 International Design Excellence Awards.

Photos by Leszek Arkuszewski

Background

Breastfeeding is a highly beneficial practice for the health of infants. The World Health Organization recommends that children be exclusively breastfed until at least 6 months, and that breastfeeding can help prevent developmental and nutritional deficiencies.

Perceptions of both the nursing mother and society are critically important for public nursing. Women who feel more comfortable breastfeeding in public spaces such as malls, restaurants, public facilities, or workplaces are 2.9 times more likely to continue breastfeeding to 6 months (Russell & Ali, 2017). Breastfeeding mothers face stigma and are still asked to move or stop breastfeeding in public. Embarrassment about this stigma remains a formidable barrier and may prevent women from initiating breastfeeding in the first place (Office of the Surgeon General, 2011).

Breastfeeding mothers continue to face subtle or overt forms of social regulation, which occur in the form of glances, glares, or comments (Boyer, 2012). The perception of these subjective norms can make if much harder for women to make the choice to breastfeed, as the avoidance of public breastfeeding can confine mothers to their homes.

Rights

Women in Ontario have the right not to be discriminated against due to their breastfeeding practices. They cannot be disadvantaged in regard to services, housing, or employment. They are also protected from harassment and negative treatment about their choice to breastfeed (Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2008). This policy on preventing discrimination because of pregnancy or breastfeeding states:

“Achieving integration and full participation requires barrier-free inclusive design up front as well as removing existing barriers. Good inclusive design will minimize the need for people to ask for individual accommodation.”

Agency

Women should have control of the decisions they make about their children’s health. This sense of agency affects whether someone will make the choice to breastfeed and how they feel about the process. Women who have agency regarding their choices may be more likely to breastfeed for longer and judge their breastfeeding experience as successful (Ryan, Team & Alexander, 2017).

Anxiety about public breastfeeding can cause a barrier for some people. Women with low self-confidence or who feel that society disapproves of public breastfeeding are particularly affected by this anxiety, and this in turn affects how long they choose to breastfeed. Populations that are most affected by these fears include young women, low income women, and immigrant women in Western countries (Amir, 2014).

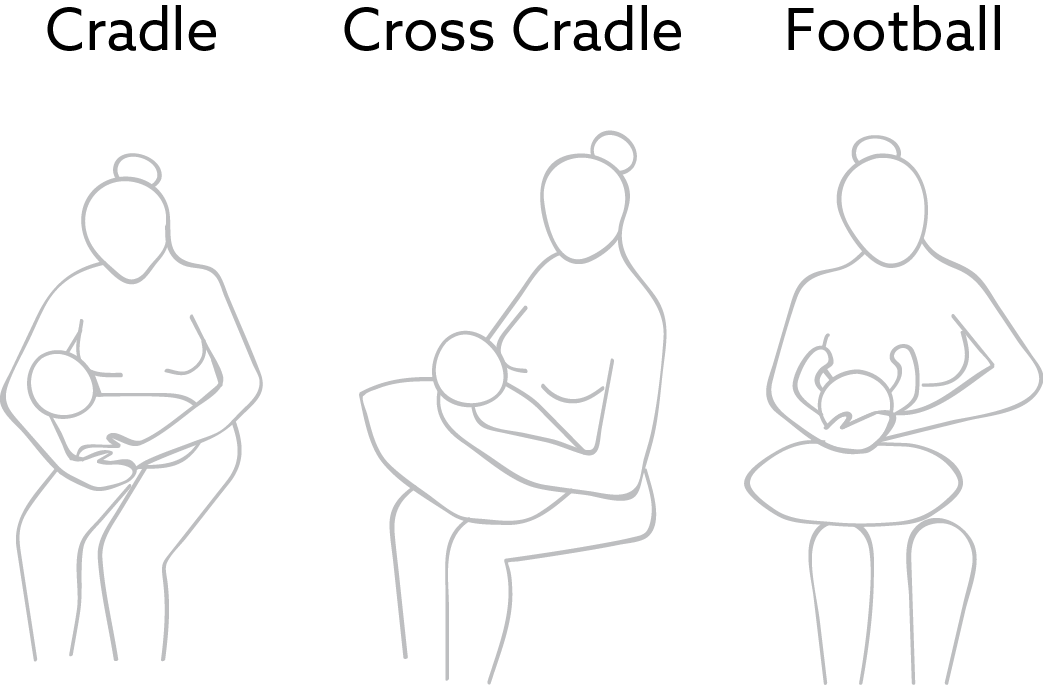

Ergonomics

Breastfeeding doesn’t happen automatically; a variety of reasons can make it difficult to achieve. Ergonomics can play a key role in this regard. Postural concerns include:

Bringing the baby to breast height

Keeping the baby close to the body to protect the joints

Changing positions regularly to alleviate strain (O’Brien, 2017)

Design

The design of this public breastfeeding seat aims to address the previously mentioned issues. It's purpose is to provide a sense of acceptance, comfort, and privacy in a public setting without removing mother and child from the social environment. The seat can be used by anyone, but its presence within a space is an invitation for mothers to breastfeed their children in public. Its use in public spaces is intended to help decrease the stigma sometimes associated with public breastfeeding.

Physical features of the Sanctuary Public Breastfeeding seat include a high armrest for upper limb support, a padded side wall for sound dampening, edge contrast between frame and upholstery for low-vision users, a reclined padded backrest, and a tabletop surface for personal belongings. The seat only has an armrest on one side to accommodate larger infants and toddlers, and to allow a sense of openness and participation in the social environment.

Process

The process started with both primary and secondary research. This included site visits, observation, interviews, literature review, and user testing and evaluation.

Secondary research was focused on inclusive design, ergonomics, comfort, and materials. Exploring inclusivity was key in achieving a holistic understanding of how to meet the needs of all the visitors to the museum. This research led to the following insights:

A good approach to evaluating a product is to identify the range of users that cannot use it. Capability levels of individuals are multidimensional and interact with each other. Inclusive design is concerned with the seamless integration of aging and disabled populations, rather than singling these populations out with “special needs” design.

Ability-based design centralizes the concept of ability rather than disability; focusing on what users can do rather than what they can’t do. Situational impairments may limit a user’s ability due to context; however the system, rather than the user, should bear the burden of adaptation.

The issue of user exclusion is multi-faceted and complex. Designers often design for those with their own capabilities, ignoring the others with different abilities.

Primary research included a site visit and observations and interviews conducted at three different museums in the Ottawa area. Part of this testing included empathy testing conducted by navigation of the Museum of History in a wheelchair. The target of these observations was seating in the museum, any issues or benefits provided by the existing seating, and how the public felt about the seating provided and what they would like to see improved. One issue that was brought up in interviews was breastfeeding within the museum environment which was the determinant for my design direction.

Questions that arose during the seat’s design included those of dimensions, comfort, perceptions of safety and privacy, spatial awareness, and the social perceptions of breastfeeding. To address these issues I conducted two forms of testing. The first was a posture analysis and observation, and the second was an online survey.

Posture analysis took place in the Canadian Science and Technology Museum. Participants were visitors to the museum. The testing included informal interview questions. As part of the process participants were asked to sit on a wooden seat base that had many accessory attachments. The categories of data investigated included physical comfort and body dimensions, perceptions of privacy, perceptions of social inclusivity, and spatial awareness.

Qualitative data was collected through an online survey. I created a short survey using Google Forms; to recruit participants, I posted it to my personal Facebook page and asked people to fill it out or share it with others. The test was shared over 20 times and garnered 360 responses from anonymous users over five days. Participants were asked about their experiences with public breastfeeding and how they were affected by different factors. Particularly informative were long-answer questions, as many of the answers revealed aspects of public breastfeeding I had not considered. It was extremely valuable to hear the voices real breastfeeding women; I felt that my understanding of the issue was much richer after reading through the hundreds of responses I received.

The following patterns were found in these answers:

Self consciousness and judgment

“I breastfeed once in public. Even though the baby was covered, people complained and I was asked to stop.”

“The glances and judgmental looks from people who don’t have a clue is what makes me uneasy about feeding my baby in public.”

Lack of seating

“Physically I get a little sore when there isn't proper seating. I take my nursing pillow with me everywhere to alleviate back pain, but it does get a little awkward hauling an extra piece of equipment around.”

Worry over making others uncomfortable

“Doesn’t bother me but I don’t want to make anyone else feel uncomfortable. It’s a shared space so I try to find a restroom but sometimes there isn’t one nearby.”

Difficulty and distraction

“Visual and auditory distractions for baby makes it hard to feed.”

Armrests and table tops

“Arm support on chairs can make it difficult to breastfeed, depending on size and design of chair since baby's legs stick out.”

“Table tops for a diaper bag are always a plus”.

Visual inspiration for the aesthetic of the seat was drawn from layers found in nature - strata that build up over time.

Ideation

These initial sketches explored methods of including privacy, adding elbow support, blocking sound, and integrating the seat into a social environment in a playful manner. These explorations were focused both on nursing mothers and individuals with issues around sensory over-stimulation such as those with autism or a traumatic brain injury.

After an initial design direction was chosen, the form and features were explored in further sketches.

Full Scale Model

A full scale model was created with dimensions based on the posture analysis results. This model was used to get a sense of how it would feel to use the breastfeeding seat.

Manufacture

The Sanctuary seat is constructed with Baltic plywood. A series of profiles is cut with a CNC, and then the slices are laminated together before the piece is sanded, finished, and upholstered.

Seating system

The overall seating system for the Canada Science and Technology Museum is pictured below. The colour of the upholstery matches the museum’s branding. Several complementary pieces are pictured with the Sanctuary seat. The cylindrical stools are the work of another student designer, and function as part of the overall seating system; the stools provide entertainment and distraction for children so their parents/guardians can use the breastfeeding seats or just sit and relax.

References

Amir, L. H. (2014). Breastfeeding in public: “You can do it?”. International Breastfeeding Journal, 9(1). doi:10.1186/s13006-014-0026-1

Boyer, K. (2012). Affect, corporeality and the limits of belonging: Breastfeeding in public in the contemporary UK. Health & Place, 18(3), 552-560. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.01.010

O'Brien, T. (2017, December 06). The Best Breastfeeding Positions for Mom and Baby. Retrieved November 15, 2017, from https://www.parents.com/baby/breastfeeding/basics/the-best-breastfeeding-positions-for-mom-and-baby-/

Office of the Surgeon General. (2011). Barriers to breastfeeding in the United States. Office of the Surgeon General (US). intelligence: Developmental limits to learning-based cognitive change. Intelligence, 56, 16-27.

Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2008). Policy on Discrimination because of Pregnancy and Breastfeeding. Ontario Human Rights Commission.

Russell, K., & Ali, A. (2017). Public Attitudes Toward Breastfeeding in Public Places in Ottawa, Canada. Journal of Human Lactation,33(2), 401-408. doi:10.1177/0890334417695203

Ryan, K., Team, V., & Alexander, J. (2017). The theory of agency and breastfeeding. Psychology & health, 32(3), 312-329.